By Elizabeth Leake (STEM-Trek)

STEM-Trek collaborated with Oklahoma State University, the University of Oklahoma and the South African Center for High Performance Computing (HPC) to plan a workshop and networking activity for technology facilitators who support education and research computing in rural regions of the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa. “HPC On Common Ground @ SC16” activities took place in Salt Lake City, Utah, November 11-19, 2016 during the annual supercomputing conference.

So why “rural,” and what does Borlaug have to have to do with supercomputing?

So why “rural,” and what does Borlaug have to have to do with supercomputing?

Norman Borlaug was one of the most important scientists of all time and the only person to have been credited for saving one billion people from starvation. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, a Presidential Medal of Freedom, a Congressional Gold Medal, and became known around the world as the Father of The Green Revolution.

Borlaug was born in 1914 in a small farming community in northwest Iowa. He lived on a 50-acre parcel with his four siblings, parents and grandparents. Only half of their land was in production, and it was difficult to make ends meet even in good years. The soil was rocky and challenging to cultivate. In a video sponsored by the United States Dept. of Agriculture, National Institute on Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA) titled “Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution, Borlaug remarked, “as we plowed, we had to keep moving boulders that seemed to reproduce each year.” The hard work gave Borlaug a strong back, and indomitable spirit.

He was 15 when the stock markets crashed in 1929. His grandfather emphasized the importance of education—he knew it would be his grandson’s pathway out of a life as a subsistence farmer.

Because he was so strong, he was an excellent wrestler in school and that’s what caught the attention of those who recommended him for a Great Depression-era academic program called the National Youth Administration. With a scholarship to attend the University of Minnesota, he would ultimately earn a Ph.D. in Plant Pathology, with a minor in plant genetics.

But Borlaug first majored in Forestry as an undergrad. Plant pathology would later become a means to an end once he realized the connection between famine and war. It was in Minneapolis where he first witnessed needless hunger. The Teamsters Union had gone on strike, and they withheld the delivery of food. When farmers tried to create a local market, riots broke out on “Bloody Friday,” July 20, 1934. Martial law was eventually imposed to restore order.

During the Dust Bowl, all vegetation died in many places. Topsoil blew like drifts of snow and buried buildings and fences that had to be raised.

The vast, U.S. Great Plains region during the “Dirty Thirties” was affected by a ten-year drought. All or parts of Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas—states where most of the nation’s wheat and other seed grains were produced—turned to dust, and strong winds caused huge dark clouds of top soil to accumulate in drifts, like snow. Livestock died, and plants that managed to emerge were stressed and therefore more vulnerable to diseases and pests.

Farmers hung on as long as they could before they packed up, and fled for greener pastures. Wherever they landed, they became marginalized members of society, and they were devastated to have lost their land, possessions and hope.

Farmers hung on as long as they could before they packed up, and fled for greener pastures. Wherever they landed, they became marginalized members of society, and they were devastated to have lost their land, possessions and hope.

Borlaug completed his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota in 1942, and worked as a plant pathologist for DuPont Chemical Company from 1941-44. According to a 2013 Borlaug biography by Ronald Phillips (National Academy of Sciences), when Pearl Harbor was attacked, Borlaug’s lab was commandeered by the war effort to “formulate adhesives used to seal containers of food and other goods dropped (by air) into the water near shorelines.”

Borlaug completed his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota in 1942, and worked as a plant pathologist for DuPont Chemical Company from 1941-44. According to a 2013 Borlaug biography by Ronald Phillips (National Academy of Sciences), when Pearl Harbor was attacked, Borlaug’s lab was commandeered by the war effort to “formulate adhesives used to seal containers of food and other goods dropped (by air) into the water near shorelines.”

By then, he was married with one child, and had another on the way. While it would have been easier for him to stay at Dupont where he would enjoy job security and more time with his growing family, he instead embarked on a quest for world peace through greater food security. The work kept him away from home for months at a time, but he never gave up the fight.

When asked to reflect on her grandfather’s career and life, Julie Borlaug (Corporate Relations, AgriLife Research at Texas A&M) said he believed “there is no science too advanced for the small holder farmer, and the most advanced science should be used in the battle against hunger and poverty.”

Borlaug set out to develop stress-resistant, high-yielding wheat varieties. Cross-breeding for the most favorable traits required scientists to combine genetic plant material and then wait for them to grow and be tested under various conditions before they could determine which performed the best. He realized it would take a lifetime to progress with such tedious work in a single lab, in linear fashion. Therefore, he proposed establishing test sites in field stations across the US and Mexico where there are multiple growing seasons each year. With help from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Mexican government, Borlaug’s vision became a reality. His distributed approach significantly expedited the process of discovery, and he was able to develop new varieties and methodologies that would ultimately increase Mexican wheat production four-fold. Mexico became self-sufficient in wheat production within 15 years, and even exported a surplus. Borlaug continued his work tirelessly in Asia and Africa, where all would eventually experience tremendous economic improvements due to his efforts.

Borlaug thought of himself as a “Hunger Fighter,” and encouraged his comrades-in-arms to continue the battle. While many of his discoveries lasted as long as 40 years, pests and diseases evolve and adapt quicker to environmental changes than scientists can develop stress-resistant plant varieties and bring them to market. Therefore, the challenge of producing enough food for the world’s growing population without further deforestation has become even more difficult with a rapidly-changing climate.

Fortunately, today’s hunger fighters are armed with big data and fast computers. Field trials are conducted at sites around the globe that grow thousands of varieties under varied conditions (maize, wheat, soy, cassava and rice, to name a few). Through memorandums of understanding among international research groups, scientists analyze shared data using supercomputers to identify highly productive and resilient genetic traits that are ideally suited for different conditions and environments (elevation, temperature, moisture, etc.). The work is often conducted remotely via high-speed networks through science gateways or domain-based cyberinfrastructure, such as CyVerse (iPlant).

Green Revolutionaries are likely to have been born in, or near agricultural regions and therefore might lack access and opportunity to train in the use of advanced computational resources, data analysis and visualization techniques. In the U.S., in terms of research dollars awarded by state, Massachusetts ranks very high, and Boston is home to 35 post-secondary education institutions. Conversely, Iowa ranks much lower. Therefore, if Borlaug had been born in Boston, it’s likely he would have become a marine biologist, or chemist who developed submarine superglue for the war effort; not the Father of the Green Revolution.

Borlaug’s roots are why we hosted the US/Pan-African Workshop titled “HPC On Common Ground @ SC16” in Salt Lake City, Utah, November 11-19, 2016.

_________________

This story was featured in HPCwire, Science Node and on the SC16 blog.

We appreciate the generosity of our sponsors and friends, including Cray Computing, Airlink Airlines (South Africa), SC16 General Chair John West (TACC), and others.

Many thanks to USDA fact-checkers, Kevin Silverstein (University of Minnesota, MSI), CIMMYT, the U.S. Library of Congress, and Julie Borlaug (AgriLife Research, Texas A&M) for their contributions.

Photography credits:

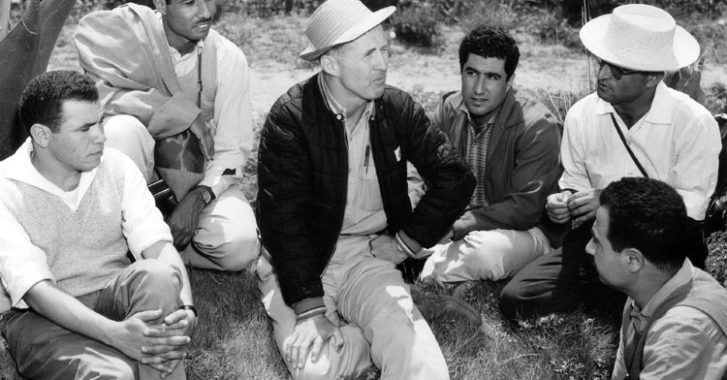

1. “Norman Borlaug with trainees,” available under creative commons license via CIMMYT.

2. “The winds of the dust bowl have piled up large drifts of soil against this farmer’s barn near Liberal, Kansas,” by Arthur Rothstein, 1936, USDA-ARS. Available under creative commons license from the archive at the U.S. Library of Congress.

3. “More Oklahomans reach California via cotton fields of Arizona,” by Dorthea Lange, 1939. Via USDA-ARS, under creative commons license from the archive at the U.S. Library of Congress.

4. XSEDE Campus Champions in 2010, courtesy of US-National Science Foundation’s XSEDE;

5. SADC Delegates visit the Texas Advanced Computing Center during SC15. Photo courtesy of TACC/STEM-Trek.